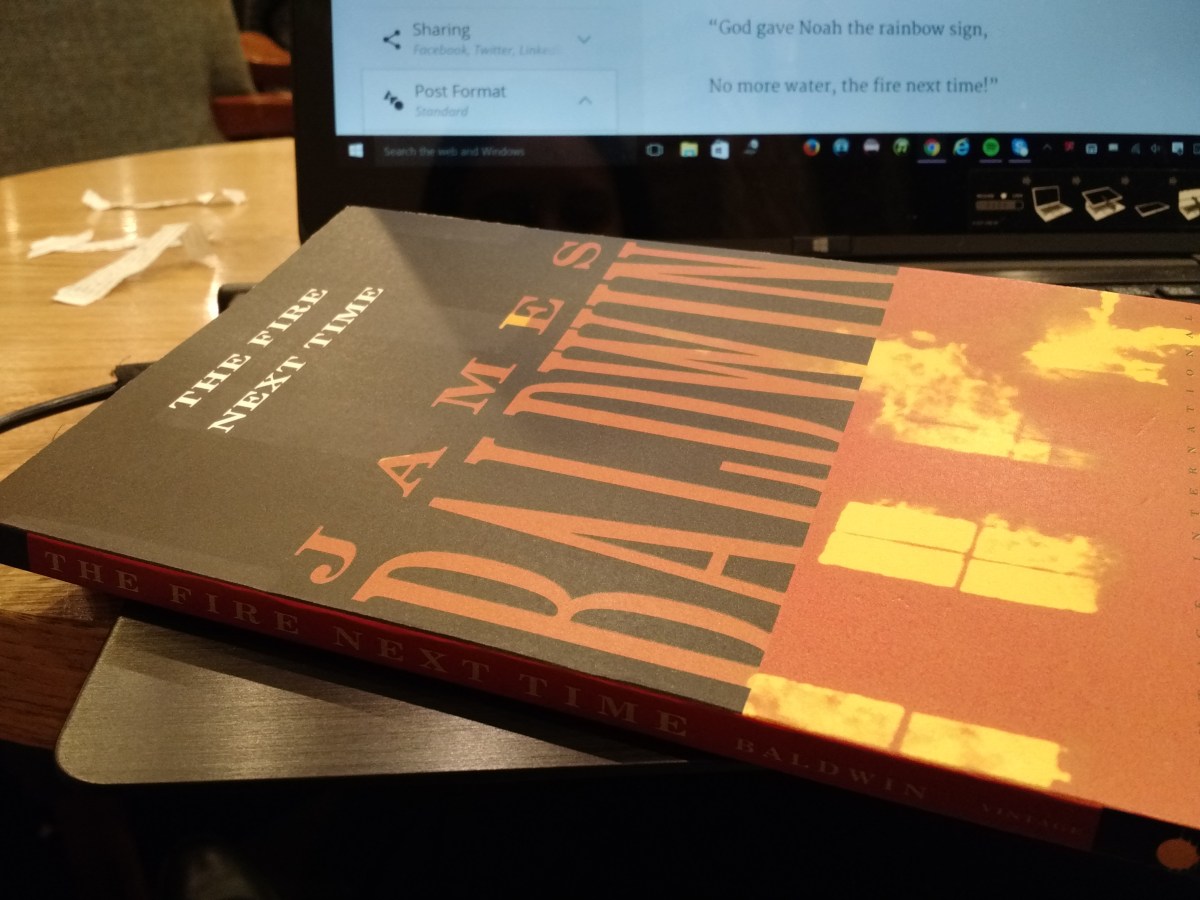

The Fire Next Time, from the inimitable James Baldwin, is a book in two parts:

-My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation

-Down At the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind

The first letter is only seven pages, and it is what (in format and content) most directly influences Ta-nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me. It’s the kind of communication that seems too well put together to be worth picking apart. Go read it.

The second letter, 90 pages long, is excerpted below. Selection is its own commentary; I’m not aiming to cloak his words in analysis. Mainly I just wanted to set down for myself the parts of Baldwin’s work that seem eerily prescient – he looks at the past with unsentimental eyes, the only way to predict the future. The Fire Next Time has a 1962 copyright. There’s something really bittersweet about the timelessness of this particular art. It’s the kind of book that you almost hope will come to feel dated, the way certain idealists hope their foundations will put themselves out of business. Baldwin doesn’t seem to hold much stock in that brand of optimism. His book is a call to action, named for a warning:

“God gave Noah the rainbow sign,

No more water, the fire next time!”

***

On being saved:

“Well, indeed I was, in a way, for I was utterly drained and exhausted, and released, for the first time, from all my guilty torment. I was aware then only of my relief. For many years, I could not ask myself why human relief had to be achieved in a fashion at once so pagan and so desperate – in a fashion at once so unspeakably old and so unutterably new. And by the time I was able to ask myself this question, I was also able to see that the principles governing the rites and customs of the churches in which I grew up did not differ from the principles governing the rites and customs of other churches, white. The principles were Blindness, Loneliness, and Terror, the first principle necessarily and actively cultivated in order to deny the two others. I would love to believe that the principles were Faith, Hope, and Charity, but this is clearly not so for most Christians, or for what we call the Christian world” (31).

Why it’s a mistake to assume that racism only harms through overt malice:

“The treatment accorded the Negro during the Second World War marks, for me, a turning point in the Negro’s relation to America. To put it briefly, and somewhat too simply, a certain hope died, a certain respect for white Americans faded. One began to pity them, or to hate them … Home! The very word begins to have a despairing and diabolical ring … see, with his eyes, the signs that say ‘White Ladies’ and ‘Colored Women’; look into the eyes of his wife; look into the eyes of his son; listen, with his ears, to political speeches, North and South; imagine yourself being told to ‘wait.’ And all this is happening in the richest and freest country in the world, and in the middle of the twentieth century. The subtle and deadly change of heart that might occur in you would be involved with the realization that a civilization is not destroyed by wicked people; it is not necessary that people be wicked but only that they be spineless” (54-55).

On recognizing the same truth about violence, but coming to different conclusions:

“When Malcolm X, who is considered the movement’s [Nation of Islam] second-in-command, and heir apparent, points out that the cry of ‘violence’ was not raised, for example, when the Israelis fought to regain Israel, and, indeed, is raised only when black men indicate that they will fight for their rights, he is speaking the truth. The conquests of England, every single one of them bloody, are part of what Americans have in mind when they speak of England’s glory. In the United States, violence and heroism have been made synonymous except when it comes to blacks, and the only way to defeat Malcolm’s point is to concede it and then ask oneself why this is so. Malcolm’s statement is not answered by references to the triumphs of the N.A.A.C.P., the more particularly since very few liberals have any notion of how long, how costly, and how heartbreaking a task it is to gather the evidence that one can carry into court, or how long such court battles take. Neither is it answered by references to the student sit-in-movement, if only because not all Negroes are students and not all of them live in the South. I, in any case, certainly refuse to be put in the position of denying the truth of Malcolm’s statements simply because I disagree with his conclusions, or in order to pacify the liberal conscience” (58-59).

How assuming the worst becomes a default state of being:

“In a society that is entirely hostile, and, by its nature, seems determined to cut you down – that has cut down so many in the past and cuts down so many every day – it begins to be almost impossible to distinguish a real from a fancied injury. One can very quickly cease to attempt this distinction, and, what is worse, one usually ceases to attempt it without realizing that one has done so. All doormen, for example, and all policemen have by now, for me, become exactly the same, and my style with them is designed simply to intimidate them before they can intimidate me. No doubt I am guilty of some injustice here, but it is irreducible, since I cannot risk assuming that the humanity of these people is more real to them than their uniforms. Most Negroes cannot risk assuming that the humanity of white people is more real to them than their color” (68).

Reread that quote. The truth of it, in the exact power dynamics it describes, is undeniable. That power dynamic still exists – witness the number of people who felt compelled to respond to “Black Lives Matter” with “All Lives Matter,” not realizing that they completely missed the point. That truth is also a useful lens to understand other power dynamics: what it feels like to be labeled an “illegal alien” in a place you’ve fought to make your home; what it feels like to be a woman in a rape culture; what it feels like to be gender fluid in a boy/girl world; what it feels like to have your love called an abomination; what it feels like to have your faith equated with terrorism … All injustice is connected.

The roots of separatism:

“And I looked again at the young faces around the table, and looked back at Elijah, who was saying that no people in history had ever been respected who had not owned their land…It is only the ‘so-called American Negro’ who remains trapped, disinherited, and despised, in a nation that has kept him in bondage for nearly four hundred years and is still unable to recognize him as a human being. And the Black Muslims, along with many people who are not Muslims, no longer wish for a recognition so grudging and (should it ever be achieved) so tardy. Again, it cannot be denied that this point of view is abundantly justified by American Negro history. It is galling indeed to have stood so long, hat in hand, waiting for Americans to grow up enough to realize that you do not threaten them” (73-74).

The pull of radicalism:

“‘I’ve come,’ said Elijah, ‘to give you something which can never be taken away from you.’ How solemn the table became then, and how great a light rose in the dark faces! This is the message that has spread through streets and tenements and prisons, through the narcotics wards, and past the filth and sadism of mental hospitals to a people from whom everything has been taken away, including, most crucially, their sense of their own worth. People cannot live without this sense; they will do anything whatever to regain it. This is why the most dangerous creation of any society is that man who has nothing to lose. You do not need ten such men – one will do” (75-76).

Every time authorities wonder how the latest strongman could have inspired such fanaticism I marvel at how those in power inevitably prove amnesiatic about its pull. Lofty heights dazzle even the most jaded eyes – it becomes difficult to remember all those still in shadow. Still harder to recall that those who feel the most powerless have the least fear.

Why those who dream of a new future must first understand their past:

“To accept one’s past – one’s history – is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it. An invented past can never be used; it cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay in a season of drought. How can the American Negro’s past be used? The unprecedented price demanded – and at this embattled hour of the world’s history – is the transcendence of the realities of color, of nations, and of altars” (81-82).

Politics make strange bedfellows; an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind; and other aphorisms that prove hate is an indiscriminate fire:

“In any case, during a recent Muslim rally, George Lincoln Rockwell, the chief of the American Nazi party, made a point of contributing about twenty dollars to the cause, and he and Malcolm X decided that, racially speaking, anyway, they were in complete agreement. The glorification of one race and the consequent debasement of another – or others – always had been and always will be a recipe for murder. There is no way around this. If one is permitted to treat any group of people with special disfavor because of their race or the color of their skin, there is no limit to what one will force them to endure, and, since the entire race has been mysteriously indicted, no reason not to attempt to destroy it root and branch. This is precisely what the Nazis attempted. Their only originality lay in the means they used. It is scarcely worthwhile to attempt remembering how many times the sun has looked down on the slaughter of the innocents. I am very much concerned that American Negroes achieve their freedom here in the United States. But I am also concerned for their dignity, for the health of their souls, and must oppose any attempt that Negroes may make to do to others what has been done to them. I think I know – we see it around us every day – the spiritual wasteland to which that road leads. It is so simple a fact and one that is so hard, apparently, to grasp: Whoever debases others is debasing himself. That is not a mystical statement but a most realistic one, which is proved by the eyes of any Alabama sheriff – and I would not like to see Negroes ever arrive at so wretched a condition” (82-83).

Living the [American] dream and being afraid to wake up:

“There are too many things we do not wish to know about ourselves. People are not, for example, terribly anxious to be equal (equal, after all, to what and to whom?) but they love the idea of being superior. And this human truth has an especially grinding force here, where identity is almost impossible to achieve and people are perpetually attempting to find their feet on the shifting sands of status. (Consider the history of labor in a country in which, spiritually speaking, there are no workers, only candidates for the hand of the boss’s daughter.) Furthermore, I have met only a very few people – and most of these were not Americans – who had any real desire to be free. Freedom is hard to bear” (88).

What we’re really afraid of:

“Behind what we think of as the Russian menace lies what we do not wish to face, and what white Americans do not face when they regard a Negro: reality – the fact that life is tragic. Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only face we have. It seems to me that one ought to rejoice in the fact of death – ought to decide, indeed, to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life. One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us” (91-92).

Baldwin says, “It can be objected that I am speaking of political freedom in spiritual terms” but he doesn’t apologize. I’m not about to apologize for the theological digression that is about to occur – what else is religion but an attempt to explain the dark? Also, those who pretend that politics is a secular activity should remind themselves how many politicians have been called saviors. I instinctively mistrust those who promise salvation; when I think of rituals that ring true, I remember Ash Wednesday Mass, reciting, “Remember you are dust and to dust you shall return” as a priest inscribes the cross on my forehead. You’re supposed to let the cross wear off on its own. Of the few Ash Wednesday services I remember actually attending, most were brief after school events which I followed up with swim practice. When I wasn’t using a cap to cover it up and chlorine to obliterate it, I was wearing the cross around my house – not exactly a public performance. The one time I went to Mass before school was senior year of high school. My AP Lit teacher, the most sarcastic human being I have ever met (and I appreciate sarcasm, so I’ve met a lot), told me: “I didn’t know you were Catholic. If I had, I would have made fun of you a lot more.” That’s how I found out he was Catholic. American Catholics, at least the Irish-inflected, Italian brand I’m most familiar with, tend to value the ability to hold their faith at arm’s length. It is brought closer for special occasions, rituals long ago dulled by a fog of incense, leaving Ash Wednesday alone rough-hewn and raw. My friends and I tended to ignore it, because it’s way more fun to decide if you’re giving up soda or candy this year than to meditate on the death side of the Risen equation. In contrast to Lent’s 40 days of solemnity, Advent feels like an extended baby shower. There are four candles on an Advent wreath: three purple, one pink. All four weeks feel like a cozy celebration. There may have been no room in the inn, but everyone has room in their heart to celebrate a baby. Lent is different. Jesus was a radical, betrayed by his friends, executed by an occupying government. The amount of blood involved in that story gives the weeks of purple a deeper hue. In that atmosphere, the one rose-colored Sunday feels joyful in a way carols can’t match – cut as it is with the sharp knowledge of what is to come.

On envy:

“The white man’s unadmitted – and apparently, to him, unspeakable – private fears and longings are projected onto the Negro. The only way he can be released from the Negro’s tyrannical power over him is to consent, in effect, to become black himself, to become part of that suffering and dancing country that he now watches wistfully from the heights of his lonely power and, armed with spiritual traveller’s checks, visits surreptitiously after dark” (96).

Redefining the definition of progress:

“I am far from convinced that being released from the African witch doctor was worthwhile if I am now – in order to support the moral contradictions and the spiritual aridity of my life – expected to become dependent on the American psychiatrist” (96).

What everyone knows it’s really about but doesn’t like to say because it’s not polite:

“Why, for example – especially knowing the family as I do – I should want to marry your sister is a great mystery to me. But your sister and I have every right to marry if we wish to, and no one has the right to stop us. If she cannot raise me to her level, perhaps I can raise her to mine” (97).

The eternal question of suffering:

“…this endless struggle to achieve and reveal and confirm a human identity, human authority, yet contains, for all its horror, something very beautiful. I do not mean to be sentimental about suffering – enough is certainly as good as a feast – but people who cannot suffer can never grow up, can never discover who they are. That man who is forced each day to snatch his manhood, his identity, out of the fire of human cruelty that rages to destroy it knows, if he survives his effort, and even if he does not survive it, something about himself and human life that no school on earth – and, indeed, no church – can teach. He achieves his own authority, and that is unshakable. This is because, in order to save his life, he is forced to look beneath appearances, to take nothing for granted, to hear the meaning behind the words. If one is continually surviving the worst that life can bring, one eventually ceases to be controlled by a fear of what life can bring; whatever it brings must be borne. And at this level of experience one’s bitterness begins to be palatable, and hatred becomes too heavy a sack to carry. The apprehension of life here so briefly and inadequately sketched has been the experience of generations of Negroes, and it helps to explain how they have endured and how they have been able to produce children of kindergarten age who can walk through mobs to get to school” (99).

The mirror of another’s eyes:

“The tendency has really been, insofar as this was possible, to dismiss white people as the slightly mad victims of their own brainwashing. One watched the lives they led. One could not be fooled about that; one watched the things they did and the excuses that they gave themselves, and if a white man was really in trouble, deep trouble, it was to the Negro’s door that they came. And one felt that if one had had that white man’s worldly advantages, one would never have become as bewildered and as joyless and as thoughtlessly cruel as he. The Negro came to the white man for a roof or for five dollars or for a letter to the judge; the white man came to the Negro for love. But he was not often able to give what he came seeking. The price was too high; he had too much to lose. And the Negro knew this, too. When one knows this about a man, it is impossible for one to hate him, but unless he becomes a man – becomes equal – it is also impossible for one to love him. Ultimately, one tends to avoid him, for the universal characteristic of children is to assume that they have a monopoly on trouble, and therefore a monopoly on you. (Ask any Negro what he knows about the white people with whom he works. And then ask the white people with whom he works what they know about him” (102-103).

What it will take:

“If we – and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of others – do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world” (105).