My current charter school organization started an initiative last year in which we talked a lot about building “tribal community” on our campuses. Thankfully, we have stopped using the term “tribal” – I don’t feel the need to tell you who was upset and why; I trust you to figure that out.

That shade aside, the concepts behind building community in our classrooms and on our campuses truly are key to effective teaching. Students can’t learn if they don’t feel safe. There is extensive neuroscience that backs that philosophy, and it is a philosophy that educators across the United States recognize to be both research-driven and ethically important.

It is naive to pretend that this is a philosophy that only matters to students. Teachers have to feel safe in the classroom too. Respect is a two-way street. It is the teacher’s job, as the adult in the room, to set a “warm but strict” tone that both acknowledges students’ innate humanity and holds them to high expectations regarding behavior (in both the academic and social realms).

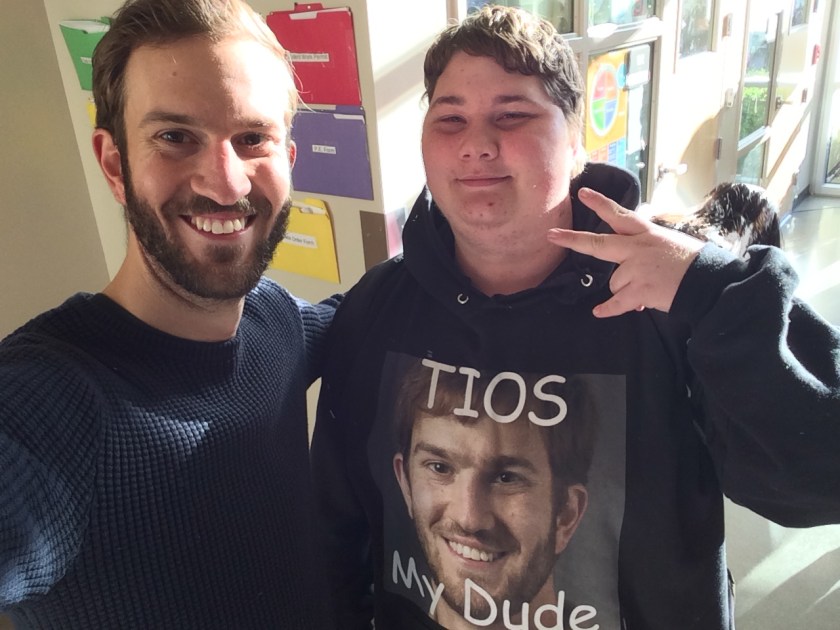

Back to the neuroscience realm: Teachers must acknowledge that students are operating with brains that are still developing; therefore, it is immensely important to be as patient as possible when dealing with students who have in any way violated the agreed-upon community norms. It’s also important to let students have a say in establishing those norms. Norms that Summit Public Schools regularly uses that I love: One Voice (listen attentively to whomever is speaking, whether that be the teacher or a classmate); Stand Up for Your Education (advocate for yourself; seek help from adults or peers when necessary to reach academic success; value your development as a lifelong learner); and This is Our School. (That one is the one that is most likely to be interpreted in a sarcastic manner by students who don’t necessarily respect the physical space of a classroom, the equipment they are given, or the physical space of the school outside a classroom; however, it is also the norm that reminds students to respect said physical spaces and to value their school community as both a community of people and a physical space for learning. Sometimes my students pronounce the acronym TIOS “tee-awhs,” and my gringa brain thinks, “Why are they pronouncing ‘uncles’ so strangely?” Then I have to remind myself that’s not what the student meant.)

All that is to say, Summit Public Schools has put an extraordinary amount of energy into trying to build a community that is based upon mutual respect between teachers and students. Does that community building always work? Of course not. We’re all human. Is it a worthwhile goal? Of course it is.

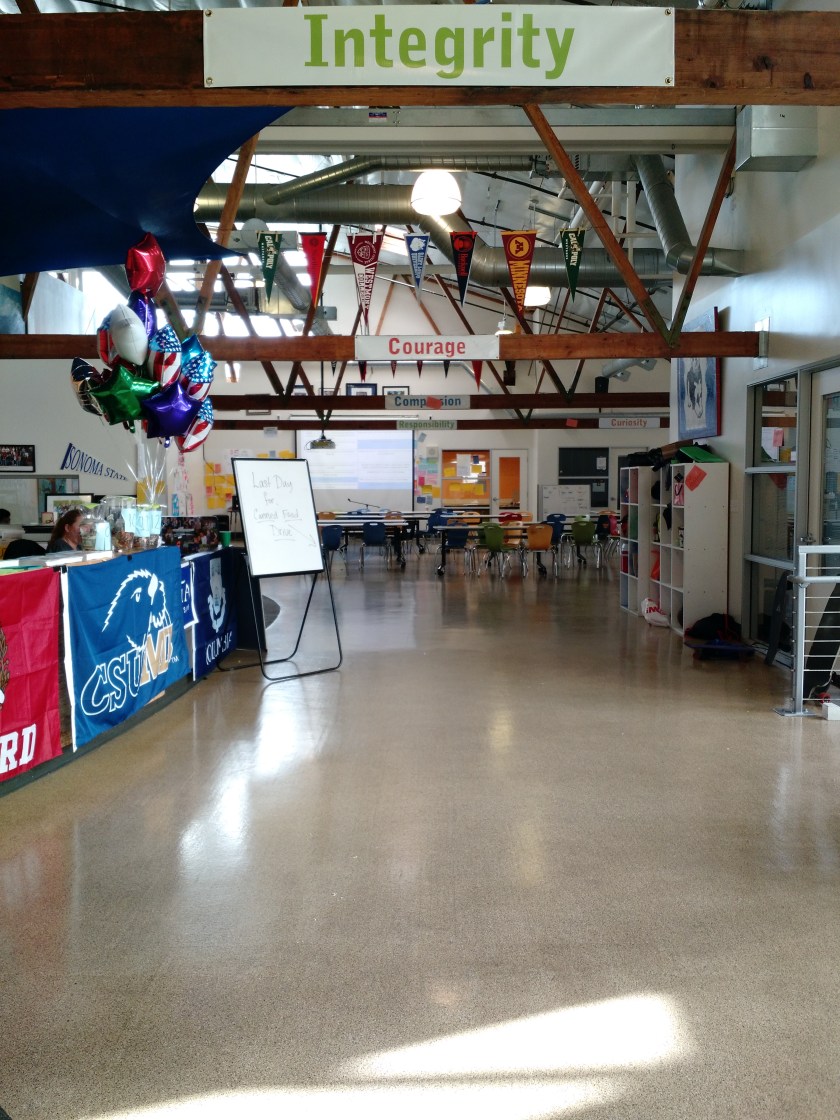

My very first teaching experience at Summit was New Student Orientation, in which we spent a lot of time trying to get incoming freshmen to understand and internalize the norms discussed above, as well as Summit’s core values (see the Character Development section of this brochure).

The six core character traits that Summit teaches (and puts up on its walls, see below), are as follows: Respect, Integrity, Compassion, Responsibility, Curiosity and Courage.

I have zero issue with that list of core character traits. That list is a large part of the reason I came to Summit in the first place. I believe that my primary job as a teacher is to help my students recognize their own brilliance and to gently (or not so gently, depending on the situation – I take both rules and procedures seriously, and I do not in any way tolerate bullying, cyberbullying, homophobia, slut shaming, sexism, racism, religiously motivated bigotry, xenophobia or anything else that interferes with our goal of creating a safe environment for all students ; I’ve had a lot of practice in both teacher glares – I won a Paper Plate Award for that one from the Rainier faculty last school year – and targeted lectures in my eight years in the classroom) nudge them in the direction of becoming better humans.

I am reminded constantly of the double meaning of the word “summit” whenever I say “Summit,” which I say a lot, considering I work at Summit Public Schools; the flagship high school, which is one of the four sites at which I currently teach, is often referred to simply as Summit; we are currently working to adopt the term “Summit Learning,” in recognition of the fact that “personalized learning” has become a roughly meaningless piece of jargon due to too many people interpreting it in too many wildly different ways; and I advise a student-produced news and commentary site located at www.summitpsnews.org.

I am reminded that we might name our schools after mountains because we think those names evoke summits of achievement and the idea that we are empowering ourselves and our students to dream big and to believe that they can accomplish anything. The word “summit” also constantly reminds me of how much work it takes for some of our students and our teachers to reach success. Not everyone has the same advantages in life. Privilege is a complex issue. It is sometimes hard to predict what kinds of privilege a particular person does or does not have. This is reason number 1,000 why “listen first” is a solid edict to live by.

My sister is currently finishing her last semester as a graduate student in the School of Education at Berkeley. The Summit school that is closest to her house is K2, and she was very confused about why the students walking in and out of that school did not appear to be lower-elementary-school-aged; so I had to explain to her that Summit has traditionally named its schools after mountains, and K2 (currently a 7th-9th grade school) is therefore named after the second-highest (next to Everest) mountain in the world.

Our organization believes in All-Org events; the most infamous of which is the before-school camping trip for all staff. I was firmly instructed when I joined Summit that our CEO believes in saying “faculty” not “staff” when referring to teachers, which is a nice nod to the fact that teachers are professionals; however, sometimes “staff” is the only applicable word for events like that, in which all employees of the organization are invited to attend.

At the All-Org camping trip last summer, school site teams were asked to create a visual representation of their mascot and to develop a team chant. If you attend Everest Public High School, you should know that your school leader is very adamant about the fact that You Cannot Name a Higher Mountain. You should also know that he told us it was OK to publish this photo. I do not have to tell you that Summit students have a thing for memes.

If you are enrolled in an Expeditions course, such as one of the courses that I teach, you should know that we created two different Griffin paintings (since our team of teachers operates on two different rotation schedules), and that I was a driving force behind the decision to cover both Griffins in glitter. The Visual Arts teachers, naturally, get full credit for how incredible those Griffins look.

All that is to say, my definition of “community” centers around school. It always has. I wanted to be a teacher when I was a bratty, know-it-all elementary school student who always had her hand in the air because I couldn’t stand the kind of silence that descends on a classroom when a teacher asks a question, and students know the answer, but no one wants to say the answer. My sixth grade teachers, who I really respected, told me, “You can do better. Go be President. We’d vote for you.”

At the time, I remember being really confused. Why would these two women, both of whom were well-respected educators, discourage me from following their example and becoming a teacher? Then I grew up and entered the real world. I discovered that teachers are disrespected across America. We are not treated as professionals. If you want proof of that, go back and read the original text of the Orwellian-named No Child Left Behind law. That entire law conceptualized “accountability” as an effort to impose punitive consequences on teachers and schools that did not measure up, as opposed to recognizing teachers’ professional expertise and empowering them to act as professionals in areas such as assessment development. Test prep companies made a lot of money from NCLB. Not very many teachers earned any extra money for their roles in helping to develop and implement standardized tests.

I now have a master’s degree in Secondary Education, with a concentration in curriculum and assessment development. When I moved to California, and I was looking for potential new career pathways, I was told by an Ed Tech company that I did not have enough experience in writing assessment questions to be worth hiring. I have developed assessment banks for the Teach for America-Tulsa (now TFA-Oklahoma) curriculum development team, for the Teach for America Tulsa Summer Institute, and (in conjunction with fellow professional educators) for my own classroom. I thanked them for their time and for the opportunity to interview.

Do I have a chip on my shoulder about the way I, and my fellow teachers, are treated? Absolutely. General Assembly members in Oklahoma publicly called teachers “overpaid babysitters.” (Here’s why that’s particulary galling. Here’s the proof that kind of harmful rhetoric is still leading to harmful actions.) Someone calculated what a teacher’s annual salary would be if we added up all the children they supervise and paid them the same hourly rate per child that we regularly pay babysitters. That graphic (and similar calculations) went viral. I think you can probably guess that the annual salary number it quoted was significantly higher than that set for Oklahoma teachers by the General Assembly and the state school districts.

What do I do when I get frustrated? First I listen to Taylor Mali. “What Teachers Make” and “I’ll Fight You for the Library” are beloved in teacher circles for good reasons.

Then I write my own work. I use this blog, or I use my social media feeds, and I try to vent my frustration in a productive way. Would you like to know what frustrates me infinitely more than the way that teachers in America are treated? It’s the way we treat students.

I’ve had too many people react to me saying I’m a teacher by saying things like “I’m sorry” or “That must be hard” or “How do you deal with those kids?” or “I’m glad someone is willing to do that job.” Guess what? Teachers are ready and willing to do that job because our students are brilliant, creative, empathetic human beings who will one day rule the world. On many days, I feel privileged to be the audience who gets to hear (or read) their impassioned work. On many days, I feel motivated to share that work with the world. I like that social media gives me a platform for that. Student voices matter.

Educators love to repeat the mantra “students first.” The best educators really mean it. I try to uphold that ideal every day. The best compliments I’ve ever received were from colleagues or students who told me I was having success on that front.

The internet and social media allow me to be part of a nationwide (and global) community of educators. That is my community. Those are my people. Students are teachers too. I learn more from my students than I learn from anyone else. Listen first. Then speak out. My definition of community includes honesty. Speak your truth.

NOTE: Photo Credit for the featured image on this post goes to Summit Expeditions teacher Aaron Calvert, who generously put up with me saying, “Please take a picture of that sign” – let’s just say more than once – after I’d already maxed out my cell phone battery taking pictures at the rally that kicked off the San Francisco Women’s March on Jan. 21.